Tomboys and Trans Kids.

Tomboys and Trans Kids.

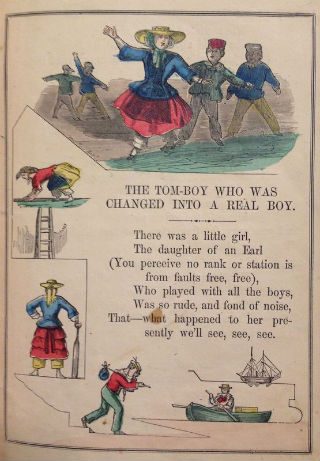

Those who follow advances in contemporary LGBT publishing may be surprised that back in the mid-1800s, transgender kids were a hot topic in children’s literature. Stories with titles like “Lucy Nelson: Or the Boy-Girl,” “The Tom-Boy who was changed into a real boy,” and “Billy Bedlow; Or the Girl-Boy” provide a glimpse back into a time when such cross-gender behaviour was not just unexpected, but taboo.

Jen Manion, an Associate Professor of History and American Studies at Connecticut College, has helped uncover this treasure trove of children’s literature. It is available for viewing at an LGBT history site, outhistory.org (see links at the end). “As a historian, I am always interested in how the study of the past can help contextualize our contemporary issues and movement,” Manion says. “I wanted to show that this issue is not new or a fad but something people have thought about for a long time. I relate to people trying to find their place when they do not conform to dominant gender norms. Childhood can be liberating if you get to express yourself and also devastating if you are punished for it.”

This literature Manion feature is from the Antebellum period of American history, spanning from the 1830s through the 1860s. They were part of a wave of children’s publishing at the time, designed to be both educational and punitive. Focusing on stories of children who defied societal expectations (whether about character, morality, cleanliness, or gender), the reports point out the ramifications of breaking social mores, including teasing and ostracism. For example, Lucy, whose “clothes were torn to pieces in climbing fences and trees,” is made to wear boys’ clothes as a punishment. Although Billy “delighted to sit with his sisters and make pincushions” and “thought himself a beautiful boy,” he eventually has his hair cut short and must cease wearing female clothes.

Although most stories feature children who eventually cease their cross-gender behaviour, Manion believes these stories “can also be read as inspiring and hopeful.

For a young person with no external validation or recognition of their gender, just reading that others felt the same way could have been life-changing… I was surprised by how rich and detailed the stories are and how many of the emotions and behaviours portrayed are not very different from what a transgender or gender-nonconforming person may experience today.”

Manion’s favourite is a story poem titled“The Tom-Boy who was changed into a real boy.” In it, the character referred to only as the “Tom-boy” is portrayed as not liking to sew and having become too “coarse” to live as a girl. She is eventually encouraged to “change her sex completely” as this was “only right” and is sent off to sea to live like a sailor. The poem concludes on a cautionary note, yet the accompanying illustration shows a happy young tomboy climbing a ship’s rope. Published more than a hundred years ago, today’s tomboys and trans boys will likely still relate.

Manion credits both the feminist movement and contemporary transgender rights movement for creating publishing space for healthy self-representation. “Today, you have many more positive portrayals of transgender youth, including stories written by transgender people. This is tremendously powerful and important.”

Witness the commercial success of recent kids’ books such as 10,000 Dresses and My Princess Boy or the trans-positive messages of the picture books by Flamingo Rampant press. While it’s doubtful that the authors of any of these books had access to the historical source material, this again proves that the theme of struggling to live true to oneself, even among children, is timeless and universal.

In fact, says Manion, “Sometimes it is easier to engage with and learn from historic sources because they are removed from present day politics. Because the stories were written before gender nonconformity was associated with either homosexuality or a transgender identity, we can see how these things were thought of in society before sexology took control of the narratives. They also help us see how the gender of children is socially constructed.”

Manion says it would be an asset to present-day researchers to know what today’s transgender kids think about these stories. Manion states, “I wonder if they would think these stories were depressing or inspiring – or both.” Manion also thinks these stories could be educational in classrooms as a teaching tool for educators looking to explain life beyond the gender binary.

Given conservative criticism that transgender children are a new phenomenon “caused” by today’s more liberal parents or the influence of LGBT adults, Manion makes the relevant point that this literature backs up the fact that “transgender kids are not a fad or a result of the modern LGBT rights movement. Rather, this research shows that these kids have been trying to carve out space for themselves to live across or between genders for a very, very long time.”

Visit the website for more: