Even if there was greater racial diversity in international dance sport, same-sex couples would not be able to dance on the competition floor

The couples walk on to the ballroom dance floor. Erect backs brace the partners’ stylised movements. Beaded gowns swirl in the coloured lights, their sequins and crystals shimmering. The sight is mesmerising, until one notices something missing. Where are the same-sex couples dancing?

The world of ballroom dancing portrayed on international dance sport competitions appears White, affluent, and heterosexual. Television shows, such as Dancing with the Stars (DWTS), portray some racial and ethnic diversity. But even in those shows, the celebrity dancers, not the professional partners, provide the diversity. The only exception is Cheryl Burke in the American version of DWTS who is half Filipina.

The popularity of ballroom dancing in countries such as Japan and China make Asians the second most visible group in ballroom dance.

Yet even if there was greater racial diversity in international dance sport, same-sex couples would not be able to dance on the competition floor. According to the 2012 World Dance Sport Federation Professional Division Competition Rules, a couple is defined as consisting of “a male and female partner”. A same-sex couple would be disqualified from competition.

As defined by the Gender and Education Association, it seems that the values associated with ballroom dancing are what social theorists would define as heteronormative:

Heteronormative … means that man has been set up as the opposite (and superior) of woman, and heterosexual as the opposite (and superior) of homosexual. It is through heteronormative discursive practices that lesbian and gay lives are marginalised socially and politically and, as a result, can be invisible within social spaces such as schools.

In a telephone interview, Claire Cutrupi, co-owner of Dance Cats, Melbourne’s only dedicated GLBTIQ dance studio, explained why:

In traditional mainstream dance sport, there has to be the leader and the follower. The leader is the male and the follower is the female. One would think that there would be a shift in this thinking. There has been evolution on our thinking about choreography and movement, but not yet in this.

In an article for The Gay and Lesbian Review, scholar J. Ellen Gainor points out that while the social traditions of male dominant and female submissive roles play out in mainstream ballroom dancing, there is nothing inherent in the dance steps that essentially male or female. She states:

Many of the steps that comprise the individual dances are executed similarly by both partners, and there is nothing inherent to the figures – other than convention – that precludes their being danced by either sex.

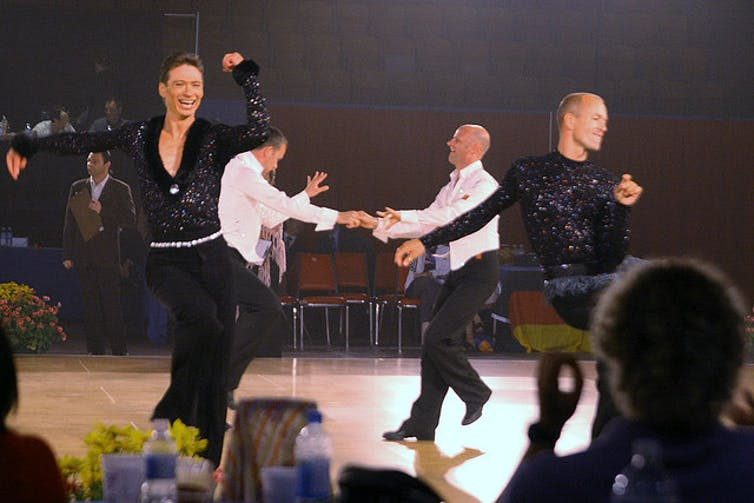

In the lead switch, the partners at pre-arranged moments re-situate their hands, exchanging positions in the dance hold to take on the other’s role. This can be a beautifully choreographed moment, as in the waltz, when the dancers assume a pose, their arms lifting up and then floating gracefully down into the new position before resuming the forward motion. Or the switch can be a rapid, staccato change, punctuating the angularity of a dance like the tango.

The disruption of ascribed gendered roles and the supportive environment within the same-sex ballroom dance community are two of its most distinct features. Gainor highlights:

The changing of lead disrupts any notion we might have of how ballroom represents “masculinity” or “femininity” inhering in a given individual; similarly, the changes of lead reflect a parity between the dancers – the ability to move seamlessly between roles and positions in a partnership of equals.

In terms of creating a supportive environment, Ms. Cutrupi noted her preference for the same-sex dance sport community over the mainstream community:

It is a very different community from mainstream dance sport. And I am protective of that culture. There isn’t as much support or fun in mainstream dance sport. It is too competitive. Everyone is out for himself. It is different in same-sex dance sport. When a competitor had to drop out of the competition in the Out Games in Darwin last year, his dance partner was left without a partner. Another competitor from Sydney put his hand up and said let’s dance together. This is what needs to be nurtured.

The introduction of same-sex ballroom dance competitions at events such as the Gay Games show the headway the community is making. Blackpool, a major site of the ballroom dancing circuit, hosts its own Same-Sex Dance Festival. In 2010, the Isreali version of Dancing with the Stars had the first same-sex female couple on a DWTS show, Dorit Milman, who is heterosexual, and Gili Shem Tov, who is lesbian.

This headway made on TV and official events is important because the spread of same-sex ballroom dancing to individual dance studios will happen top-down. Cutrupi states that while some studios are becoming more open, there is still at lot of discrimination and homophobia both outside and within the GLBTIQ ballroom dance communities:

As the same sex dancing become more acceptable in mainstream dance sport, it would be filtered down through to individual studios.

As a feminist, the filtering down of the ethos of equality and fluidity of gender roles is something I would appreciate in my own dance lessons and competitions. When I asked Ms. Cutrupi what individuals could do to help push the same-sex ballroom dance movement forward, she said:

You can say, “No, I want to learn the leaders role.” Or the followers role, which ever is the opposite role given your gender in traditional dance.

Yet, the one barrier that remains for both the mainstream and same-sex worlds of ballroom dance sport is the cost. Ballroom dancing is priced for the affluent. Private lessons can range from $60-$75 each. There are medal fees, competition fees, as well as tickets to social events. At the level of the professional dancer in dance sport competition, the costs can be quite prohibitive. Ms. Cutrupi listed her expenses per dance event, of which there are several a year:

- Standard ballroom dress: $2,000

- Latin ballroom dress: $2,000

- Fake spray tan: $45

- Fake eyelashes and makeup: $50

- Fishnet stockings: $45

The heart of ballroom dancing is the unity of movement between the dance partners. This unity can be achieved regardless of the gender of the partners. Same-sex ballroom dancers should not suffer discrimination either off or on the dance floor. The World Dance Sport Federation should allow the them to be fairly judged in competition based on the artistry and technical proficiency of the only thing that matters—their dance.

I will take the first step in un-doing the traditional ballroom power dynamics of lead and follow by asking to learn to lead in my next dance lesson. ![]()

Elizabeth Dori Tunstall, Associate Professor, Design Anthropology, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.