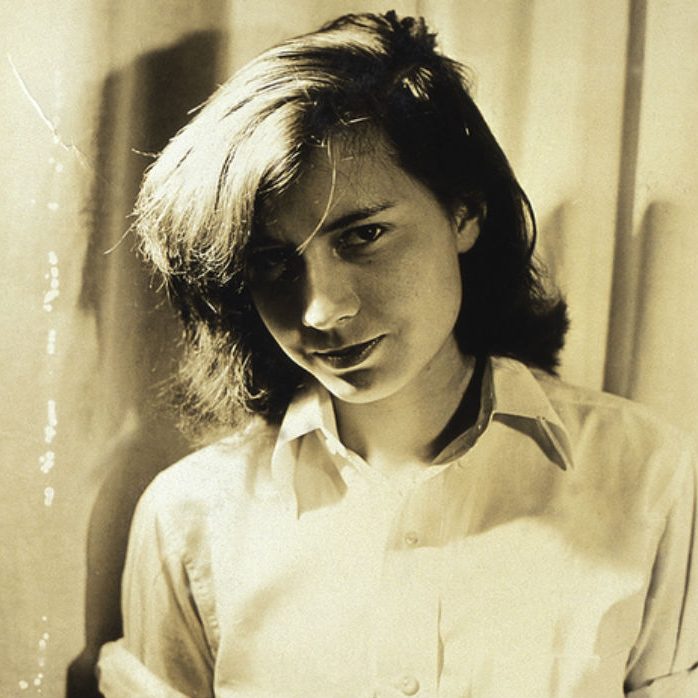

Patricia Cornwell, the world’s best-selling crime writer, continues to hit the mark.

Out of darkness comes light. It’s an old adage but one that might apply to the life and art of Patricia Cornwell, America’s most successful contemporary crime writer.

Life these days sparkles for Cornwell: Her books have sold more than 100 million copies; she is happily married to Staci Ann Gruber, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School; her work takes her around the world and into the arms of adventure. But it wasn’t always so. Life has been quite dark for this master of crime fiction.

Patricia Carroll Daniels, born in Miami and raised in North Carolina, came from a family fractured by emotional abuse and mental illness. She ended up in the foster care system, worked hard to establish herself, at times struggling with her body image and her sexuality.

She married one of her English professors, Charles L. Cornwell, who was 17 years her senior; they separated in 1989. She was misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder. She has been besieged by legal problems, battling everything from a DUI to a tangled accusation of plagiarism launched by a lesser-known writer, Leslie Sachs. (When the court found his claims to be baseless, Sachs created a slanderous website accusing Cornwell of many things, including being a “neo-Nazi” lesbian stalker with high-level connections!)

Add to this having to sue her accountants for financial mismanagement (Cornwell won the case), plus being the subject of a “tell-all” book, Twisted Triangle, about her affair with a married FBI agent in the 1990s (the tagline is “A Famous Crime Writer, a Lesbian Love Affair, and the FBI Husband’s Violent Revenge”), not to mention facing accusations in the British press that she is “obsessed” with the unsolved crimes of Jack the Ripper, and it’s clear that Cornwell has been a victim in her lifetime, not unlike one of her own characters.

And her success, while making her rich and famous, has deepened the inherent darkness with which she engages during the course of her research.

So when I speak to Cornwell, she seems almost surprised that my line of questioning is so sunny. But I don’t wish to rattle skeletons, find out where the bodies are buried, or ogle the corpse.

There’s plenty of scuttlebutt about Cornwell online, if you want that. I want to know how Cornwell—a lesbian Southerner—became incomparably successful in her field, and what, in her heart, made it possible.

It was while working as a reporter for the Charlotte Observer that Cornwell, who always loved language, began covering crime. Through her friendship with the evangelist Billy Graham and his wife, Ruth Bell, Cornwell wrote her first published book, A Time for Remembering: The Story of Ruth Bell Graham, in 1983.

After taking a job at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of Virginia, where she worked for six years, first as a technical writer and computer analyst, Cornwell churned out three detective novels—all of which were rejected by publishers. She did not give up.

“I think you just keep doing the only thing you know how to do. The one secret that really helped me when I started writing these books is that by the time I realized my last book was going to be totally rejected by everybody, I was well into the next one. So I just kept going. And if I hadn’t done it that way, if I had waited to be judged by the opinion of a handful of people, I probably would’ve quit.”

Looking back, she acknowledges, “Those books should not have been published. I was still trying to figure out what I was doing. They were contrived stories, because I just didn’t understand the real world of crime and violence, the real world of anything.

I take that back: It’s not that I didn’t understand those things, it’s that I didn’t want to write about them.”

Working with the byproducts of violence, day after day—why would she also want to write about it? “I didn’t want to show you what I was actually seeing, experiencing—not only in my life but in the work at the medical examiner’s office. It was so harsh and graphic and vivid and scary. I didn’t want to write about the monsters.”

And then she called up a female editor who had rejected her books and asked her if she should just quit. The editor told her no and offered some advice that would serve Cornwell well: “First of all, the lady medical examiner is a minor character, but she’s your most interesting. Why don’t you make her the main character? And two, the stories you’re telling—is that what you see in the morgue? I want to see what you see.”

After that conversation, Cornwell got off the phone and asked herself if she could go there—walk around in Dr. Kay Scarpetta’s bloodstained shoes and show the world exactly what she sees in the gruesome world of forensics.

“And that was Postmortem, and that is what I’ve done ever since, and that is why it works,” says Cornwell. “Here’s the thing: Whether it’s about social issues, human nature, crime—whatever you want to talk about—just try to tell it like it is.”

A Scarpetta book is graphic and gory and also fun to read because it hooks the reader and lingers on the nitty-gritty: not just the unexpected forensic details but also the characters, the way they talk, move and think. Cornwell lays bare their fears and deeds and motives, no matter how horrible.

Her latest Scarpetta book, Depraved Heart, is no exception. I read the entire volume in two sittings. Inspired by the Gothic novelist Wilkie Collins, Cornwell knows how to leave readers craving the next installment. But the form and the technique have hooked her, too, and changed her as a person.

“In terms of how I live my life, how I think, how I adapt to certain situations, yes, my experiences have absolutely changed me. For one thing, when you see enough trauma…I’m extremely sensitive to violence and cruelty and very aware of my surroundings because of the thousands of cases that I’ve seen.

I mean, I know what kills people, both things that are random and things that are really horrible, and if you’ve seen that in the flesh enough, it does change you.”

She won’t let you in her car unless you wear a seatbelt. It’s not OCD, rather a touch of PTSD. “Your brain gets programmed differently if you’ve been through certain experiences,” she says.

But perhaps the most fascinating result of Cornwell’s on-the-job training is her female characters: Dr. Kay Scarpetta, her lesbian niece Lucy, and the hyper-villainous Carrie Grethen.

“I don’t know where they came from—not any of ’em,” she says. “I may have created them or channeled them, or whatever you want to say, but they also have created me. These characters have helped me discover so much about myself. So they make me better and I make them better. It’s very reciprocal.”

Before becoming a crime writer, Cornwell was averse to anything science-based, dropping chemistry and computer science in college. Now she reads up on science, flies a helicopter, studies surveillance techniques, ballistics, and all manner of weaponry.

“I wouldn’t go to a funeral because I was afraid of dead bodies, and then what happens? I do all these things because I decided I needed to learn. It’s amazing what you can decide you can do, if you need it.”

But when I think about Lucy and Carrie—both lesbians, both razor-smart, both FBI-trained, both athletic—it’s hard not to see the similarities between them and Cornwell herself. Is she sure she doesn’t know where they come from?

“I really don’t. There’s not any one character who is based on any one person that I’ve ever even met, much less known. I’m sure, if I really thought about it, there must be certain traits of people I knew along the way, particularly when I was getting started, but no, that’s what’s so magical about fiction.

Sometimes these characters are like walk-on actors—they just show up in your mind. And some of them hang around for a long time and some of them disappear. It’s a magical process that I really don’t understand. But the more you open yourself up to it and don’t try to control it, the better off you are and the more it works for you.”

The Scarpetta books are very visual and, as successful as they have been, it pains Cornwell that they have not yet been adapted to the screen. “It’s been really, really frustrating.

And it’s not for lack of trying, that’s what a lot of people don’t know.” Cornwell reveals that the first Scarpetta option actually happened before the first book even came out, in 1989. Since then, the project has “gone from one production company to another and it’s become a mountain nobody can climb.”

I throw around dream casting ideas for her characters—Jodie Foster as Scarpetta, Kristen Stewart as Lucy. Cornwell approves. But she’s also keen to get across the symbolic value of Lucy for lesbian readers. “You have to look at Lucy as a little bit of a metaphor for a young, modern female—we’ve kind of gone from Nancy Drew to The Hunger Games, so who are we, as immortally young women?

There’s a lot more going on with women that age—20s and early 30s— than there was when I was at that age. In terms of options and confusions—even gender or sexual orientation—we’re open to think about these things in a way that—when I was coming along you weren’t gay, you were simply a spinster.

There was no such thing as a gay woman. I’d never heard of such a thing in the little town I grew up in. So we’ve come a very long way in terms of what we can discover about ourselves and we can discuss.”

I find Lucy very strong and intelligent, willful but mysterious, with that same ambiguity one might read into Cornwell’s own biography, the battle between light and dark, destruction and survival, which are themes Cornwell’s own publicity plays upon.

She acknowledges that Lucy “can potentially be a bad, bad person, but part of embracing our power as human beings—I say this about women—part of that is embracing the potential for evil and destruction that you can do.

“I mean, some of my worst characters are women, and absolutely my best ones are. I’ve always said I’d watch Charlize Theron play anything, and one of the reasons that Charlize Theron is so powerful in Monster is that you see a highly attractive, intelligent human being reach into the deepest abyss in the soul and pull out something that’s ugly, something that’s just in them.

But maybe we all have that in us somewhere. And so I say that to women because we are striving very hard to be good, to excel, to be the best in the world at what we do, but part of understanding that is to look at all the facets of who and what we are.

“Look for the monster in you, if you have one. That’s what Lucy represents. She is a bold and unflinching look at what we are capable of as women, and the difference between Lucy and Scarpetta is Scarpetta has more of an inbuilt sort of control system where she’s not going to cross certain boundaries that Lucy would. But maybe if Scarpetta were born 20 years later, she would be crossing some of those, too. It’s hard to know.”

While Cornwell denies that her characters are avatars for herself, they are ways with which to explore “stuff about me, too. What am I capable of? And it’s really important to me because I don’t want to do harm. I’ve always been very self-scrutinizing about, ‘Is this story OK for me to tell, or am I making problems worse?’

And a couple of my books, like Predator and Book of the Dead, where I went to the third-person point of view, I started to get a little wobbly in terms of not feeling comfortable. ‘Maybe I went a little too far here, these are too violent.’ So I know that I’m capable of doing things that are damaging, and at the same time I don’t want to, either.

I guess what I’m trying to say is it’s a different way of looking at empowerment. Women can be the hero, but you can also be the worst person that we’ve ever seen in literature.”

The narrative drive of Depraved Heart is nothing if not a battle between good and evil, and a battle of wills among its trio of female protagonists. The author shares her characters’ strong will.

“That’s one of the things that I would particularly say to women: Do not be passive, go out and do something, even if you think it is tiny and small. But stay in motion, be active, be full of wonder, explore the world, and ask questions that no one else ever has. That’s what I try to do.”

Though in the libelous mind of stalker Leslie Sachs, Cornwell herself remains a dark and dangerous figure, in her own life, and certainly on the phone, she is generous and open, speaking happily about the sources of light in her life, especially love.

She “could not be more pleased” at the advent of marriage equality in this country, even though she married Staci Ann Gruber in Massachusetts back in 2005. Like many lesbians her age, she didn’t see the current advances in LGBT rights coming.

“I spend a lot of my time in very rough-and-tumble worlds where they don’t really hang out rainbow flags. Very conservative areas where I’m doing firearms and weapons research, hanging around mostly very macho men.

And I don’t have any trouble at all, never have, because we’ve always just known each other as people. The rest of it doesn’t enter into it. Who they’re married to or who I’m married to—we’re all just people.”

But in Gruber she has found the true love people hope for. “I certainly did. Aren’t I lucky? And it had nothing to do with gender, in terms of being just lucky that you’ve found somebody who is your soul mate.

And that’s the whole thing with relationships—at the end of the day, the two of you should make each of you better and that is absolutely true with us.”

She and Gruber share similar belief systems, worldviews, interests, and causes, says Cornwell. She especially approves of Gruber’s agenda to “leave the world better than she found it” through psychiatry.

Even though the couple is, by anyone’s standards, rich, they prioritize non-materialistic goals. (Cornwell funds scholarships and donates to several educational institutions.) And even though she’s enjoyed a friendship with the Bush family and donated to the Republican Party, she’s supported Democratic candidates, too.

Currently, she thinks that Hillary Clinton is the most qualified presidential candidate. “I think it’s time to have a woman president, for God’s sake. It can’t be just any woman, but we need one. We need a different perspective. Hello, it’s time.”

When Cornwell turned 50, she had an epiphany about her sexuality: It was time to come out of the closet, fully. “One of the best things I learned from Billie Jean King, probably 20 years ago—we were sitting in a restaurant in New York City, and we had this very discussion.

I said, ‘But you know I don’t really talk about it much, I really don’t want to discuss my private life like that in public.’ She said, ‘Wait till you turn 50, you will feel very differently about everything, including what you stand up and are counted for.’ And you know what? She was right. If nothing else happens as we get older, for God’s sake, tell the truth, tell the truth, tell the truth.”

With her 60th birthday around the corner, I ask her if she expects a new epiphany. “I hope there’s always going to be epiphanies. I think the only good thing you can say, the best gift about getting older, is you get insights. You’re given little treasures you wish you’d had a long time ago.

The aging process is not fun, and anyone who says it doesn’t bother them, it’s hard for me to believe that’s true. I don’t like it when my car gets dings and dents and the tires wear out. So why should I like getting older?

“But I do like the insights, the moments where you have realizations that are just a richness that you feel for knowing that, and wishing you had known that a long time ago. I always say I don’t want to go back to being in my 30s. I really don’t.

I don’t want to live all that again. I like who I am today. But I sure wish I’d known back then what I know now. But everybody says that… I’m kind of glad we can’t edit our lives, because I don’t think they’d be what they should’ve been if we could edit everything we did, like a film.”

We’d never have had Scarpetta if Cornwell hadn’t agreed to get her shoes a little bloody. And neither of them shows signs of stopping, in fiction or in real life. “I plan when I’m 80 years old to drag my carcass off in my helicopter flight helmet and wish everybody a good day,” laughs Cornwell.

“Women have got to stop believing the myths of how we lose our power as we get older. There are other ways to have it. To adapt, to take care of your health. There are certain realities we need to take care of, particularly due to the weather system known as hormones.

They usually pack up and walk off the job, which is not very fair, but we don’t have to take this sitting down. We don’t have to decide that we have nothing to offer anymore because we can’t have children. The world is not kind about women getting older.

We need to get reminded that older women are sexy too, and part of it is power and experience. So what, if you have some lines on your face? Older men are sexy. How come they are and we’re not? It’s the way we’re conditioned. I think we have to figure out a way to rewrite that memo.”

And after 23 Scarpetta books, not to mention a dozen or so others, and perhaps one day that film adaptation, Cornwell is just the person to do it.