David Bowie changed so many queer lives.

I’m not a prophet or a stone aged man/

Just a mortal with potential of a superman/

I’m living on…Quicksand

Sunday night. Always a dead night. Monday looms with each passing hour. The weekend recedes. A night of familial togetherness for some, anomie and alienation for others.

I’d just finished live-tweeting the Golden Globe Awards when a woman I know tweeted that David Bowie had died.

David Bowie as the Sphinx #RIPDavidBowie by Brian Ward around May 1971 #history #art #archaeology #music #fashion pic.twitter.com/mkM1XYG8zY

— Ticia Verveer (@ticiaverveer) January 11, 2016

Ridiculous.

Another social media hoax, I tweeted back, wondering again why people did such things. It had only been New Year’s Eve when the hoax about Robert Redford had torn through social media. A few months earlier it was Carlos Santana. And Jeff Goldblum. Plus, Bowie’s new album, “Blackstar” had just dropped on Friday. January 8–the singer’s 69th birthday. No one dies right after releasing a new album. Things like that do not happen.

How could it be, though? How, how, how?

News guy wept when he told us Earth was really dying/

Cried so much that his face was wet/

Then I knew he was not lying – Five Years

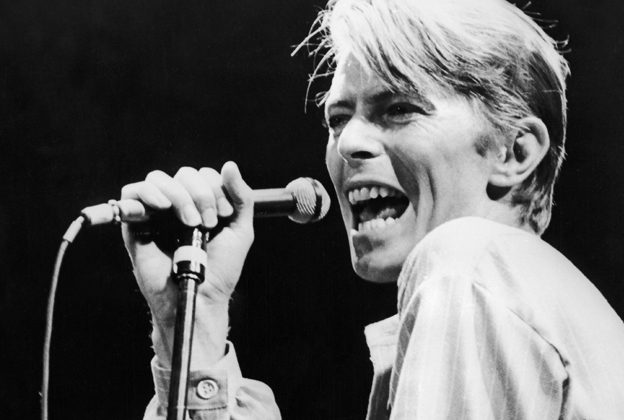

The troubadour of my teenage years through my middle age was indeed dead.

Cancer. A secret 18-month battle. Hidden. No big reveal for tabloid TV vultures. No declarations of fighting it. No public hair loss. No emaciation or bloating. No reprise of Bowie’s unpleasant end in “The Hunger” as the virile, forever-young vampire ages overnight and becomes someone we don’t recognize. None of that. The last photo of Bowie by Jimmy King mere days before his death looks like the Bowie we always knew: fashionably dressed, fabulous hat (no one wore hats like Bowie), rakishly bared ankle. His whole body’s in motion. He looks like he’s going somewhere.

He was.

Bowie was beautiful and larger than life and then he was gone and it was as if he’d been abducted by aliens or turned to stardust, but it didn’t seem even a little real.

It still doesn’t.

It’s too late

– to be grateful

It’s too late

– to be late again

It’s too late

– to be hateful –Station to Station

I don’t love celebrities. I don’t idolize anyone. Writing about pop culture often feels like an anthropological experience for me. It’s fun, but it’s not more. It’s background, not foreground. Yet there’s that handful of people who are more than their pop icon status. The ones that touch you.

None of them had been there at the Golden Globes. At least not for me. A mostly tedious night with a lot of disappointments, like “Carol” being shut out. Taraji P. Henson won. That was heartening. So did Leonardo DiCaprio. He’s one of the good guys. Gave the best speech of the night acknowledging Indigenous and First Nations Peoples (and knew to call them First Nations) as he accepted the award for “The Revenant.” I like Lady Gaga and Sam Smith, but I don’t love them, even though I appreciate her support for the LGBT community and his coming out and some of their music moves me.

But David Bowie?

David Bowie changed my life.

David Bowie changed so many lives.

You’ve got your mother in a whirl

She’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl

Hey babe, your hair’s alright

Hey babe, let’s go out tonight

You like me, and I like it all

We like dancing and we look divine –Rebel, Rebel

That song was our anthem, the way Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way” is now. Except “Rebel, Rebel” was 40 years before Gaga. Imagine hearing that lyric in your childhood bedroom when you were a baby butch or a young flamer?

You can’t, really. Everything was different then. Hidden. A mere five years beyond Stonewall, which still had barely influenced anything past New York and San Francisco. The closet was still our world.

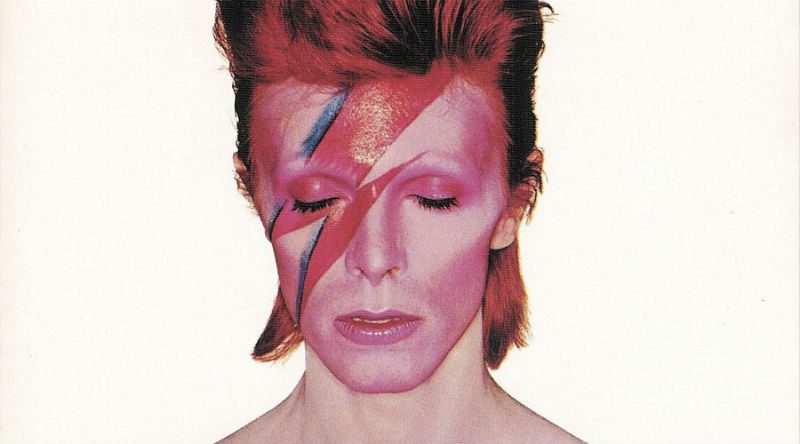

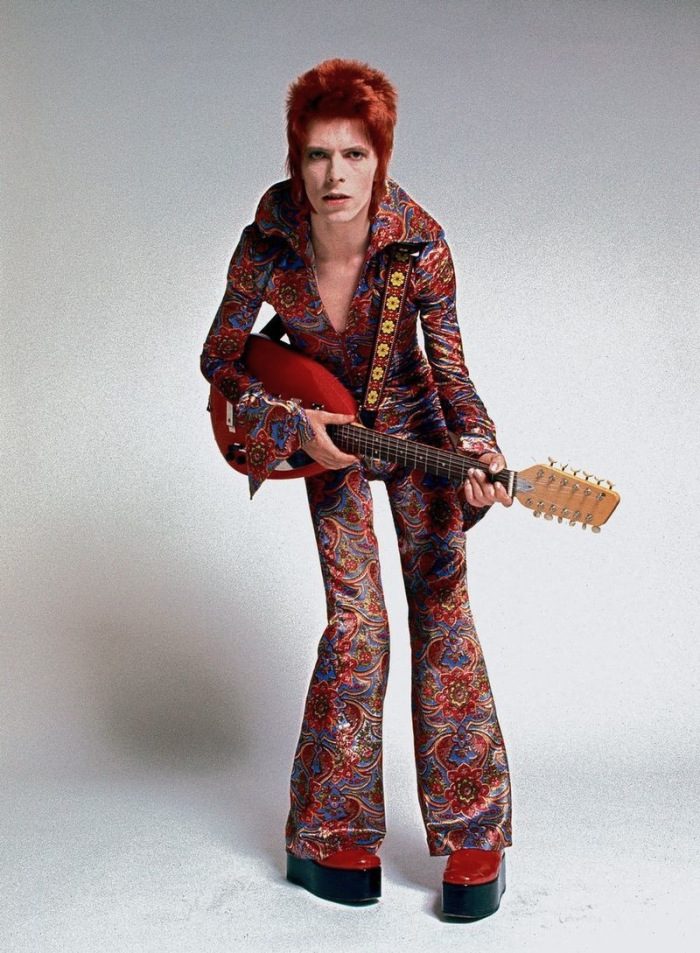

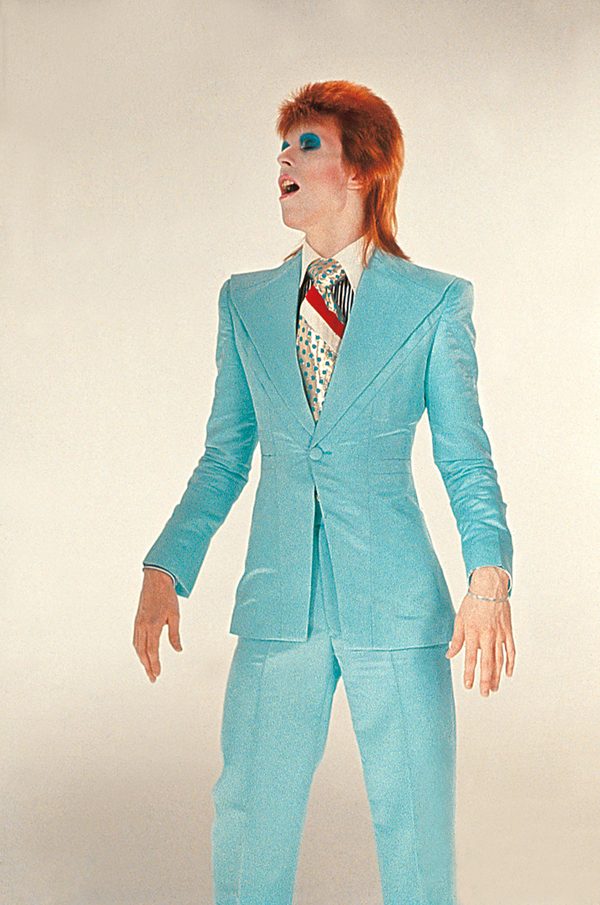

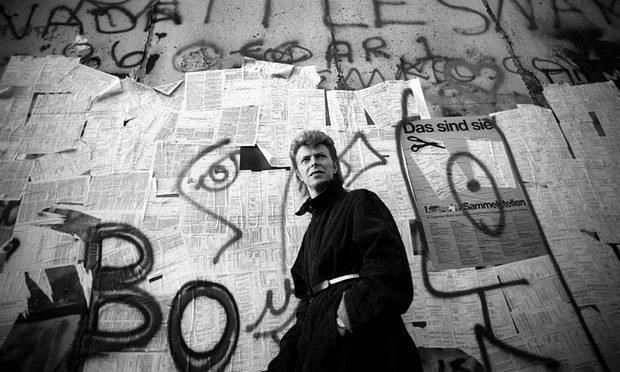

But there he was. Bowie. Short spiky hair. Makeup. Clothes from another place–maybe another planet altogether. Two years later Bowie starred in Nicholas Roeg’s “The Man Who Fell to Earth” and it was easy to believe he was the title character–sinewy, mysterious, and otherworldly. He liked women. He liked men. He didn’t care if people called him gay. Later, years later, he would say it may have been a mistake, saying that, since people got so caught up in it and he really loved women and the bi thing was more of a flouting of convention, but who cared by then? When he’d been our bisexual androgynous god, he had led us forward, taken our hands and brought us into the light.

His light.

Those eyes of his–he’d been in a fight as a kid and one had been damaged irreparably, leaving the pupil permanently dilated. Seeing something others couldn’t see. Seeing those of us always shoved to the margins, pushed to the shadows. We all have a story about him. We all have a place where the music touched us, or we thought he saw us at a concert, or we just felt connected.

Oh you Pretty Things

Oh you Pretty Things

Don’t you know you’re driving your

Mamas and Papas insane –Oh You Pretty Things

It’s impossible to explain how huge David Bowie was for us, then, the young queers of the 1970s and 1980s, like I was, like my friends were. The boys were given permission to put on makeup and still be male. The girls were given permission to cut their hair short and spiky and still be female. He allowed us to play with gender way before we ever heard the now hackneyed terms “non-binary” and “gender fluid.”

It’s impossible to articulate how just seeing David Bowie, The Eternal Androgyne, made things possible for us. He was the icon we could point to who validated our reality as perhaps Elvis had for a generation before ours. We couldn’t be Bowie, but we could play with his look, change up our own. We could be who we were. We could be ourselves.

Talented . Unique. Genius. Game Changer. The Man who Fell to Earth. Your Spirit Lives on Forever! ðŸ™ðŸ»â¤ï¸ #rebelheart pic.twitter.com/k3k3lfL3Bv

— Madonna (@Madonna) January 11, 2016

If you say run,

I’ll run with you

And if you say hide,

We’ll hide

Because my love for you

Would break my heart in twoIf you should fall into my arms

And tremble like a flower –Let’s Dance

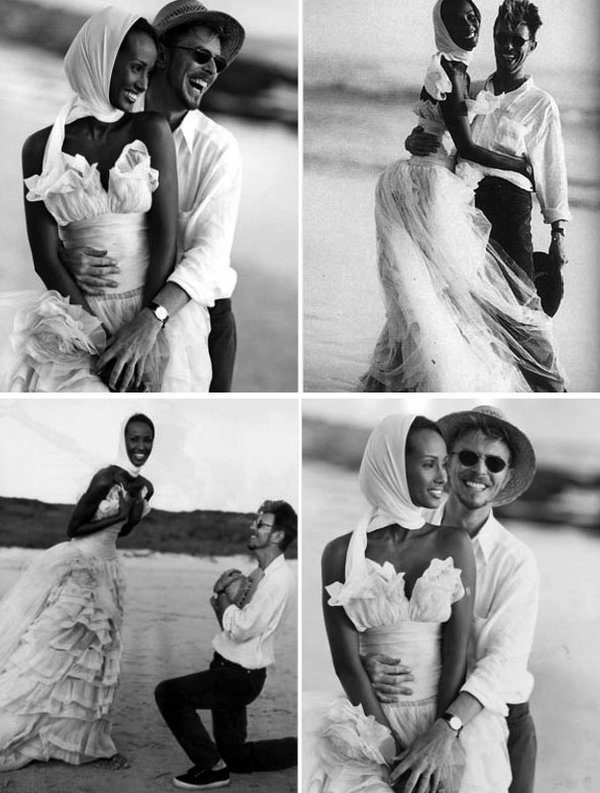

It wasn’t just us. The queer kids. It was everyone. Bowie was one of those rare artists whose arms were opened wide to embrace those working their way up. Or those he thought were already there. He was ready to help other artists and did, regularly. His friends and often his lovers were people of color. In 1992, Bowie married the love of his life, Somali supermodel Iman.

Bowie was anti-racism. It wasn’t lip service. In 1982, a year after MTV was founded, Bowie challenged MTV host Mark Goodman on the network’s refusal to play black musicians on their channel.

“David Bowie: “Why are there practically no blacks on the network?”

“David Bowie: “Why are there practically no blacks on the network?”

Mark Goodman: “We seem to be doing music that fits into what we want to play on MTV. The company is thinking in terms of narrowcasting.”

David Bowie: “There seem to be a lot of black artists making very good videos that I’m surprised aren’t being used on MTV.”

Mark Goodman: “We have to try and do what we think not only New York and Los Angeles will appreciate, but also Poughkeepsie or the Midwest. Pick some town in the Midwest that would be scared to death by… a string of other black faces, or black music. We have to play music we think an entire country is going to like, and certainly, we’re a rock and roll station.”

David Bowie: “Don’t you think it’s a frightening predicament to be in?”

Mark Goodman: “Yeah, but no less so here than in radio.”

David Bowie: “Don’t say, ‘Well, it’s not me, it’s them.’ Is it not possible it should be a conviction of the station and of the radio stations to be fair… to make the media more integrated?”

Wow. To make things fairer.

Like he’d done for us.

We had so many good times together. He was my friend, I will never forget him. 2/2 pic.twitter.com/9xfPj88x8b

— Mick Jagger (@MickJagger) January 11, 2016

Let’s dance,

Put on your red shoes and dance the blues

Let’s dance,

To the song they’re playin’ on the radio

Let’s sway,

While color lights up your face

Let’s sway,

Sway through the crowd to an empty space –Let’s Dance

Bowie wasn’t post-politics. In 1987 he performed at the Berlin Wall. Of the performance, he said, “It was one of the most emotional performances I’ve ever done. I was in tears. We kind of heard that a few of the East Berliners might actually get the chance to hear the thing, but we didn’t realize in what numbers they would. And there were thousands on the other side that had come close to the wall. So it was like a double concert where the wall was the division. And we would hear them cheering and singing along from the other side. God, even now I get choked up. It was breaking my heart. I’d never done anything like that in my life, and I guess I never will again.”

I, I can remember (I remember)

Standing, by the wall (by the wall)

And the guns, shot above our heads (over our heads)

And we kissed, as though nothing could fall (nothing could fall)

And the shame, was on the other side –Heroes

The reviews of Bowie’s final album have been strong. Rolling Stone called it, “a spellbinding break with [his] past, a headlong plunge into electro-acoustic jazz, an album that is lyrically inscrutable, thrillingly strange and undeniably brilliant.”

The Wall Street Journal called it, “A work of staggering genius.”

In the UK, The Telegraph says Bowie is breaking ground again–this time on his death bed–although no one knew that. “This time he is venturing once more into the outer limits of pop, with a gorgeously inscrutable avant jazz sci-fi torch song, all slippery drum’n’bass rhythm, two-note tonal melody with hints of Gregorian chant, shifting time signatures, churchy organ and spaced out wandering sax–like Ornette Colman on a moonwalk. And just when you think it can’t get any stranger, it turns into a bluesy ballad of mourning. ‘We were born upside down, born the wrong the way round,’ Bowie sings with enigmatic conviction.”

“Lazarus” is the most incredibly compelling track on the new album. Like all those early songs, like that early soundtrack of our gay lives, “Lazarus” takes us to our next place.

Look up here, I’m in heaven

I’ve got scars that can’t be seen

I’ve got drama, can’t be stolen

Everybody knows me now

David Bowie was an architect of our escape from the prison of hiding ourselves at a time when what we most needed was something past politics, something tangible, something we could see and reach for–a queer future. We needed a hand to hold, we needed someone who not only saw us, but welcomed us.

That was Bowie.

Mourning him, we should “put on our red shoes and dance.” We should celebrate his life and its impact on us. We should remember these words from the anthem he gave us–one of so many, over so many years, one that said we were loved, no matter who we were.

Goodnight, tweeps. So very sad. It was more than the music. It was the door he opened for us. #RIPDavidBowie ♥♡♥ pic.twitter.com/wUWhlQUSw2

— Victoria Brownworth (@VABVOX) January 11, 2016

You want more and you want it fast

They put you down, they say I’m wrong

You tacky thing, you put them on

Rebel Rebel, you’ve torn your dress

Rebel Rebel, your face is a mess

Rebel Rebel, how could they know?

Hot tramp, I love you so

‘The struggle is real, but so is God’: See Iman’s poignant David Bowie tribute