Three Steps to the Best Care.

Three Steps to the Best Care.

1. Take a Friend

Never go to the hospital alone. This is advice I give to everyone, not just queer folks. Never go to the hospital alone. Say it with me “Never go to the hospital alone!” Got that? Never go to the hospital alone.

It’s tempting if you’re one of the strong and silent type dykes–and you know who you are–to admit yourself quietly if you have a problem. Who needs a fuss? But it’s not about making a fuss, it’s about having someone else with you who isn’t sick and/or vulnerable. That person can fetch you things, get more ice water, forage for food in the neighborhood if the hospital food is inedible, etc.

Perhaps more importantly, they can advocate for you if a conflict or unexpected situation arises. You don’t want to go into the hospital with expectations that everyone you’re going to meet will be a raging transphobe or homophobe. However, if you do encounter such a person, having a witness and someone to ask questions or talk to other staff people for you will make a huge difference in how the interaction feels to you as the patient and how the situation ultimately goes down.

2. Take A Notebook

I always feel ridiculous giving this advice, because it seems so simple. Eye-rollingly simple.

That’s not too far from the truth and here’s why: the hospital staff keep records but those are for their use, not yours. In the event of any kind of problem, having notes about who you talked with, what they said, who did what procedures, etc can help you resolve the situation much more quickly.

I suggest keeping these notes in a bound composition notebook (the ones with the black speckled covers, you can often find them at dollar stores) with the time and date above each entry. Write with a black pen and no cross-outs and if there are going to be multiple people taking notes, it’s helpful to sign your entries. Even if you don’t need it during your hospitalization, it can be helpful as a reference later as part of your medical history. Also when the hospital sends you the patient survey after discharge, you can fill it out with notebook in hand, and mention the specific staff members who were helpful or unhelpful.

3. Take A Load Off

Self advocacy as a hospital inpatient can seem like a full-time job, even if you have a friend along to assist you and speak up with you when you’re too sick or annoyed or exhausted to do it yourself. If you need more back-up, it’s helpful to know what staff member to approach.

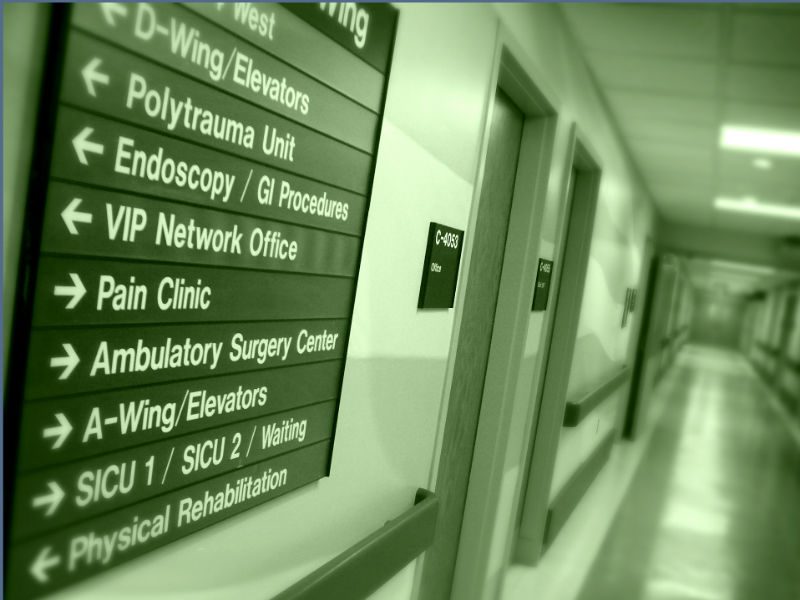

On most inpatient floors, your first line of defense is the nurse manager. There is a nurse manager physically present at the hospital 24/7, and while the person may be overseeing more than one unit on the overnight shift, during the day their office is probably somewhere within the unit or close by. You can approach them with questions or problems that you haven’t been able to resolve with the bedside staff.

Additionally, if you need help 9-5, you can ask to speak to someone in the patient advocate office. You can get this number either from the nurse’s station, from a member of the security team, or on the hospital website. Often the patient advocate has access to resources to smooth over difficult situations (the ability to validate parking comes specifically to mind) and to facilitate communication between staff members, patients and families. They can also refer you to other types of advocates within the hospital such as the pain management team or ethics board.

Finally, if your problem is not resolved and the problem is the kind of situation which might be a liability for the hospital, the final big guns are the folks in risk management. Risk management has one job: keep the hospital from getting sued and often have the power to cut through layers of hospital bureaucracy to help you find some resolution.