Transgressive lesbian photographer, Honey Lee Cottrell, addressed the Lesbian Gaze.

What is the lesbian gaze?

It’s how lesbians see each other irrespective of and in defiance of men. It’s how lesbians see each other when we are alone and we are the only ones looking. It’s how lesbians see each other as butch and femme, androgynous and gender-non-conforming, not as the male gaze defines us.

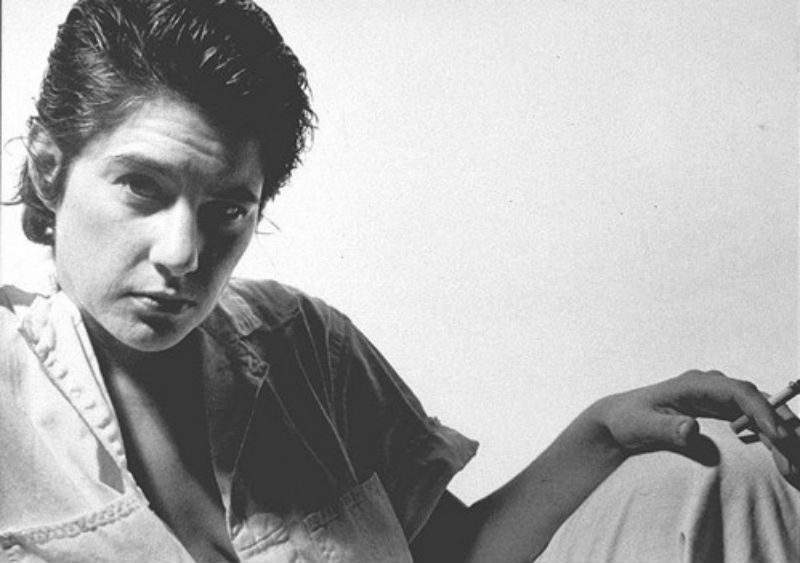

Honey Lee Cottrell–photographer, filmmaker, eroticist, butch lesbian, woman-lover–was a pioneer of the lesbian gaze. She died of pancreatic cancer on Sept. 21 in Santa Cruz, surrounded by her lesbian family and friends, but she left us with a body of work that celebrated lesbianism in its many woman-identified guises.

I only met Honey Lee once, when she was visiting one of my best friends, the late photographer and art historian Tee Corinne, with whom she had been partnered. Honey Lee was handsome and earthy and exuded a kind of strength that pulled you in.

For years she and Tee revolutionized the lesbian gaze together, each creating images of lesbians that were radical for their honesty, searing sensuality and their lesbian POV. These were not images created for male titillation: these were images created for lesbians by lesbians. In those photographs, we saw ourselves–for perhaps the first time.

Tee and Honey Lee photographed the practice.

In-text from the blog she was writing as she herself was dying of cancer in 2006 and recording the images of her lesbian life, Tee wrote, “In 1975, the year in which I most fully came out, I started making self-portraits that combined my own image with that of a lover.

Honey Lee Cottrell was my beloved at that time, and together we explored ways to make images that read as lesbian. In some of these pictures, I am nude and she is partially clothed. In one, I have my hand on her thigh and am looking into the camera as she looks at me.”

We had never seen photographs like that before.

Honey Lee and Tee talked about their relationship in the 1976 documentary We Are Ourselves, directed by Ann Hershey.

When Honey Lee later partnered with writer and lesbian “sexpert,” Susie Bright, they worked together on still another groundbreaking enterprise, the lesbian sex magazine “On Our Backs.” In their seven years living together in what Bright wrote of fondly as “The House on Bessie Street” in San Francisco in the 1980s, Bright put out the magazine and Honey Lee illustrated it with images of lesbian sexuality made especially for women.

As Bright wrote, “The best and most outrageous of ‘On Our Backs’ pictures were conceived and often shot at Bessie Street. This is where Honey Lee Cottrell, my partner, and OOB’s staff photographer, became a legend.”

It was Honey Lee who suggested a “Bulldagger of the Month” centrefold for the magazine. Brenda Marston, her archivist at The Human Sexuality Collection at Cornell University quote Honey Lee, who explained the butch dyke centrefold was intended to “stand this Playboy centrefold idea on its head from, I would say, a feminist perspective…What would I do if I was a centrefold and how can I reflect back to them our values [as lesbians]?”

This bold and transgressive idea meant transforming the standard-issue, made-for-the-male-gaze image of femaleness and replacing it with “not the regular kind of centrefold, but something that will make a difference, shake people up, show the other side of the mirror.”

Our side. The lesbian side.

For those of us who were on the front lines of what became known as the “Lesbian Sex Wars” of the 1980s as writers and artists, it was a time of coming out as sexual beings and Honey Lee Cottrell was one of the premier documentarians of that time.

Gone were the faux lesbian images of straight male porn. Instead, we were given the real bodies of real lesbians, bodies we could almost touch, they were so vivid and so real and so us.

So lesbian.

Honey Lee Cottrell was born in Astoria, Oregon, in 1946, and grew up in Michigan. In 1966 she left home and never looked back, moving to San Francisco with her first lover. San Francisco embraced her as she embraced it.

A week before her death, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors declared “Honey Lee Cottrell Day,” honouring her work as a butch lesbian photographer, filmmaker, sex educator, and co-founder of “On Our Backs.” For her lesbian family and friends who knew she was dying, it was a lovely, if bittersweet, tribute to an icon of the city’s LGBT, but especially lesbian, community.

Honey Lee said it was a “humbling” honour.

Brenda Marston of The Human Sexuality Collection at the Cornell University Library where her papers are archived said that Honey Lee studied at the National Sex Forum and was a member of San Francisco Sex Information in the 1970s.

With Tee Corinne and Joani Blank, she co-authored “I Am My Lover” in 1978. The book was a “feminist celebration of masturbation.” She was also a co-founder of the Lesbian and Gay History Project, founded in 1978 in San Francisco.

In 1981, Honey Lee graduated from San Francisco State University with a BA in film studies. She directed “Sweet Dreams” (National Sex Forum) in 1980 and was the cinematographer for Fatale Video, now Fatale Media, the first lesbian porn/erotica company, founded by Nan Kinney, a co-founder with Honey Lee, Susie Bright and Debi Sundahl of “On Our Backs.” Fatale submitted the first lesbian porn film o the Frameline Film Festival in 1985–and it was shown.

It’s almost as if Honey Lee Cottrell was creating an atmosphere of lesbian sex in San Francisco in from the early 1970s through to the end of the 90s as she photographed her lovers, her friends, lesbian sexuality. She was shifting the (male-driven) narrative of what lesbians looked like and what lesbian sex looked like–a narrative we always knew was false, we always knew was about what men wanted to see, not about who we actually were, and replacing it with the lesbian gaze and the lesbian POV.

Honey Lee documented a time and place. She covered decades of lesbian and gay life in San Francisco with her first camera, the one she fell in love with, a 35mm Nikkormat. Her still photography appeared in many publications, including “Sinister Wisdom,” the SAMOIS book “Coming to Power” and “Nothing But the Girl: The Blatant Lesbian Image.”

She exhibited her photographs throughout the Bay Area over the course of four decades and her work was shown at 848 Community Space in San Francisco, the Bacchanal in Albany, California, The Gay and Lesbian History Society of Northern California, the NAME gallery in Chicago, and her images were part of Cornell University’s Speaking of Sex exhibition.

A few weeks before her death, Honey Lee made a video about her original vision for “On Our Backs.” She is painfully thin, yet she still exudes that strength as she talks about the “psycho-sexual map of lesbian life.”

Honey Lee Cottrell addressed us, the lesbian viewer. She always looked directly into the camera in her self-portraits and in her lesbian portraits, her subjects did the same.

In her final days, Bright notes Honey Lee was able to go out one day and walk in the redwoods. It was a fitting metaphor, for Honey Lee Cottrell was herself a giant and her work and the change she created in lesbian images will remain a tribute to a community she loved and nurtured for decades.

She is survived by her mother Patricia Cottrell, brother Michael Cottrell, daughter Aretha Bright and her life companions Melinda Gebbe, Amber Hollibaugh, and Susie Bright.