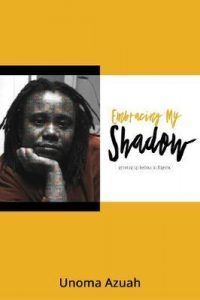

Unoma Azuah’s Embracing My Shadow, the first lesbian memoir from Nigeria, is an inspiring testimony suffused in sensuality that illustrates how a young woman can find oases of erotic love even within a severely homophobic society.

Unoma Azuah’s Embracing My Shadow, the first lesbian memoir from Nigeria, is an inspiring testimony suffused in sensuality that illustrates how a young woman can find oases of erotic love even within a severely homophobic society.

We caught up with Azuah to learn more about her journey growing into an affirming sexuality.

Something I found refreshing is that the environments are so rich with lesbian energy, whether it’s in the sheltered convent high school, your university or Lagos. What allowed you to create such an affirming lesbian-centered world, despite all the intolerance?

I didn’t really have an agenda except to tell my story. And it wasn’t all gloomy. There were beautiful moments I shared with some beautiful women. I wanted to present a balance. It was a mixture of bright moments and dark moments. It speaks to the purity of love, the beauty of it that looks beyond the judgment and the morality. And it can be discovered anywhere, in wartime, in a convent, in a garden, in a marketplace. Even all the repression in Nigeria could not stop it.

You don’t spare strong expressions of self-hate, but it feels like erotic joy ultimately wins out and is the book’s emotional touchstone.

I just feel that at the end of the day light conquers darkness, that no matter how dirty and bruised and broken one is, there is healing that has to do with owning oneself. Darkness tried to subdue me, but I decided to heal.

An irony to me is that while being a lesbian in Nigeria is dangerous and you describe being in constant fear of exposure, being queer can also provide a shelter in a world where heterosexual men appear unconscious at best and sexually threatening at worst.

I had the greatest freedom of my lesbian life in the convent boarding school because it was an all-girls school and I barely had to deal with any man. When I got to college it was miserable for me because the natural environment that was predominantly women was yanked away and I was thrown into this glaring heterosexual world where I was told you need to have a boyfriend. Have you tried it? No? Then something is wrong with you. When I got to Lagos I was more or less anonymous. I did have a lot of heterosexual men who tried to take advantage. When I had to depend on them for employment or money, I could face some sort of humiliation. But there were spaces where I felt safe.

How has indigenous Nigerian spirituality helped you to counter Christian spiritual intolerance? You seem deeply connected to the river goddess Onishe.

I was lucky to have spent a lot of time with my grandmother. She was the greatest force in my life, the most affirming and nurturing woman. I was exposed early to African spirituality through her. She was a latecomer to Christianity. She was the one who would tell me you are special, that you are different doesn’t mean anything. You are the type of person that the gods use to convey a message to heal, to prophesize. You are beautiful and a child of this goddess Onishe and she will always protect you.

The memoir’s final section brings in your human rights work for the LGBT community in Nigeria that ultimately endangers you and leads to your leaving for the U.S. How important was it to include your activist story in a memoir about love?

It’s very important because growing up I didn’t have any role models. There were few stories about lesbians and where they did exist, they were always negative. Nobody was speaking up and I wanted to speak up. That led to my activism and since I felt quite early that I can write, that became the tool of activism that I decided to use. There has been no literature for young lesbians to reach out to. A lot of Nigerian lesbians now write to me and thank me for the memoir and also for the writing I have done before, the poetry and short stories.