The film that launched lesbians onto the big screen turns 30!

Do you remember where you were when you first saw the 1986 film Desert Hearts? I was a teen with a part-time gig in a video rental store, years away from coming out—mainly because I wasn’t sure if it was possible to be a lesbian.

As a budding movie critic with an encyclopedic knowledge of films, I knew that lesbians always ended up dead, discarded or despised—at least onscreen. Older lesbians may recall movies like The Children’s Hour where Shirley MacLaine hangs herself in the attic because she is mortally ashamed that she loves Audrey Hepburn, or The Fox where Sandy Dennis is crushed by a falling tree and her lover Anne Heywood goes off with Keir Dullea. Or Personal Best, where Mariel Hemingway falls for athlete Patrice Donnelly while training for the Olympics and their relationship is derailed by straight men.

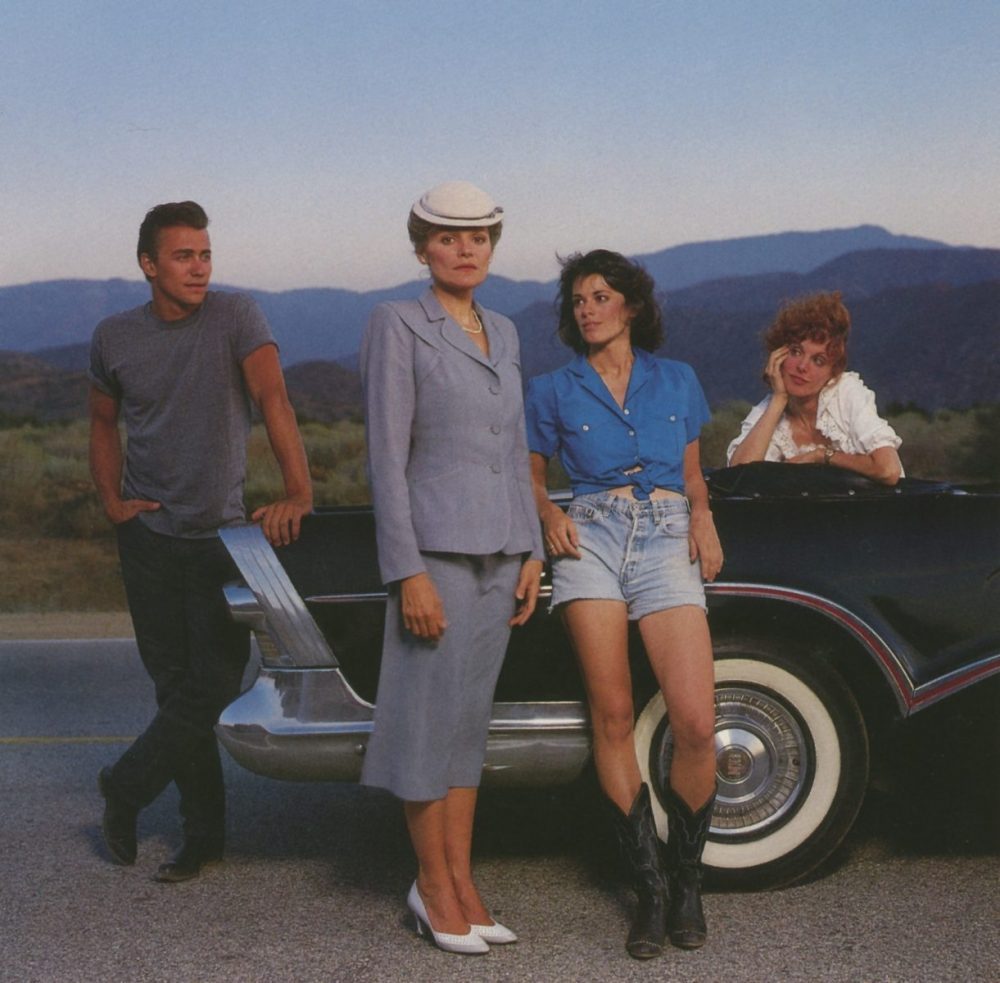

Watching Desert Hearts—on VHS!—changed all that. The romantic drama, about an English professor who travels to Reno for a quickie divorce and meets a spunky change girl with whom she falls in love, offered a different narrative. Heartfelt performances by its good-looking female stars Helen Shaver and Patricia Charbonneau, its nostalgic 1950s music soundtrack, its free-spirited Southwestern aesthetic, and a glimmer of a happy ending—all gave me a sense of hope, if not enchantment.

The film suggested that the road ahead of me wouldn’t terminate in suicide or compulsory heterosexuality. Desert Hearts did for lesbians what Thelma and Louise did for feminists—without the car going off the cliff.

I’d assumed that only women over 40 appreciated Desert Hearts, but my wife, who was barely school age when the film came out, has owned the DVD for years and values it for the same reason I do: its simple and non-pathological explanation of the existence of lesbian love.

It’s a film that speaks across generations of women, and director Donna Deitch is aware of its impact. “There are many women who come up to me everywhere where there are screenings, and they know who I am, and they start to tell me these personal stories—and this has been going on for three decades.”

Deitch, who hails from California and studied film at UCLA graduate level, had “significant motivation” for making the film, she tells me in a recent phone interview.

“Every film I’d seen about two women in love or falling in love or afraid to fall in love, always ended up in a bisexual triangle or suicide. And so I wanted to make a universal love story that happened to be between two women. Because that sort of seemed to me quite normal. I didn’t really see why people ought to kill themselves or become heterosexual just because they were falling in love with somebody of the same gender.”

Indeed, Desert Hearts is possibly the first feature film with fully-rounded female characters who are attracted to each other without that attraction being contested by a male.

“They get on the train together,” says Deitch of the ending. “We don’t know how long they’re going to be together, but they do leave Reno together and we know it will be at least as long as 45 minutes and maybe for a lifetime, or somewhere in between that.”

How the film came to be was rather serendipitous, for Deitch was given Jane Rule’s book Desert of the Heart by a friend. “I read it seven times in a row and I thought, I think this is the story I want to make because it has everything that I’m looking for and I think would make a fantastic movie.”

She used her house as collateral to raise the budget and wouldn’t let herself even consider that the project might fail. She also didn’t consider making a fantastic “lesbian movie.” It would just be a fantastic movie, period. “What is a lesbian film, first of all?” she ponders. “I’m not quite sure what that is. Is it about lesbians, and does it have to be at least two, and if there is just one lesbian in it, is it still a lesbian film? Some people think it’s a film made by a lesbian but I don’t think that’s what it is. I know what a lesbian love story is. I think of Desert Hearts as a lesbian love story.”

Deitch’s own sexuality and beliefs remained in the background during the release and promotion of the film. She was part of the women’s community in Los Angeles, the hub of which was the Woman’s Building, a community arts centre founded in 1973 by straight feminist and lesbian artists. She certainly identified as gay, but the Samuel Goldwyn Company, to which she sold the finished film, urged her to not discuss her sexuality openly “because it would distract from the story.” In 1986 the AIDS crisis was at its peak and there was “a vast amount of homophobia at the time, homophobia in urban places that are all but gone now,” she recalls. “Things have changed so much but that homophobia and that fear were rampant in every aspect of making the film, including the distribution. But I was always out. I mean, I wasn’t trying to get a journalist to speak about my sexuality because I didn’t think that was necessarily interesting. But I’ve always been out.”

The Goldwyn Company also urged Deitch to cut down the climactic love scene but she refused and “never cut a frame of it. That scene is a standout scene and most people felt it really worked. I still think it works. I think it’s part of the reason the film holds up as a universal love story and all sorts of different people relate to it.” The scene is the radical heartbeat of the film; the moment when what ‘lesbian’ is and means and feels like is confronted by both characters. It is considered exemplary for how a lesbian love scene should be directed, and Deitch’s approach to it was carefully considered. She studied many types of cinematic love scenes and quizzed Helen Shaver and Patricia Charbonneau about their willingness even before they were hired.

“Firstly, I had to know they were completely committed to it,” says Deitch, “didn’t have any kind of reservations about doing a scene of this sort. Secondly, I scheduled their love scene on the 30th day of a 31-day shoot, so that we would know each other as well as we could in the course of the shooting. And I talked with them in depth about how important to me it was to have this scene be a real scene like any other scene—with a beginning, a middle, and an end. The structure of a working scene had to be inherent in this love scene and we talked a lot abut how we were going to accomplish that.”

Deitch accomplished her vision. Desert Hearts had a “magical” production during which the cast and crew bonded, and the film was a commercial success, garnering positive reviews from even some top tier critics. “Oprah Winfrey saw the film and the next thing I knew she was hiring me to direct a miniseries for television called The Women of Brewster Place,” says Deitch, who went on to have a TV career for the next 25 years, directing shows such as NYPD Blue and Grey’s Anatomy as well as Winfrey’s new series, Greenleaf. In between, she made one personal independent film called Angel On My Shoulder, a feature documentary about her best friend Gwen Welles who died of cancer.

Deitch is planning a return to directing features, starting with A Strange Piece of Paradise, which is a true-crime story adapted from her partner Teri Jentz’s memoir. Also in the works—a Desert Hearts sequel!