The film begins with the raw sound of charcoal on canvass, women’s hands, and Marianne’s (Noémie Merlant) voice advising her students how to draw the beginning aspects of a portrait.

(Spoilers Ahead)

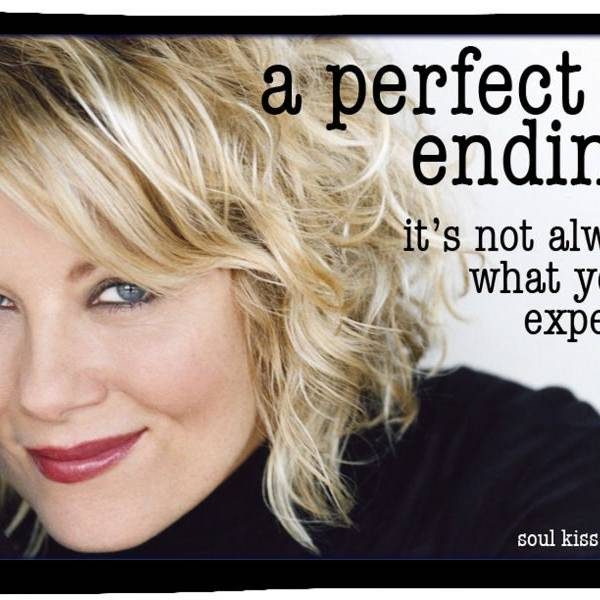

Marianne acts at the model/teacher posing for her students and is the first full image we see. A painting propped behind her students and their easels catches her attention. It is a of a woman in a field with the bottom of her dress aflame.

A student asks, “What is it called?” To which Marianne responds, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” beginning her memory/retelling of the choices made which lead to the painting.

Marianne’s retelling has her arrive at an island where we learn she has been commissioned to paint the daughter of a Countess (Valeria Golino) who wishes to use the portrait to garnish approval for a marriage between her daughter and a Milanese suitor.

Marianne knocks on the door of a castle and Sophie (Luàna Bajrami) answers it. Sophie (the housemaid) leads her up the stairs to a dimly lit room and says, “It was a reception room. I’ve never seen it used” before leaving Marianne to settle in.

Marianne learns the daughter she is set to paint is not the daughter who was supposed to wed the Milanese suitor. The sister of Marianne’s muse death by suicide (in a similar manner to the myth of Sappho’s death) when she learned of the arranged marriage. The daughter who Marianne is meant to paint has just been brought home.

The following day, Marianne and the Countess make the agreement that Marianne will paint Héloïse (Adèle Haenel) in secret as she has already avoided being painted by refusing to pose for a prior painter. Marianne will act as a walking companion and paint Héloïse at night. It turns out that painting in the 18th century takes time, light, and preferably a subject that will sit while you paint. Marianne’s determination and encouragement from Sophie leads her to get closer to Héloïse as a way to better understand her.

Sciamma evokes the female gaze to supplement dialogue as Marianne and Héloïse go on walks together.The gaze is fragmented as Marianne is unable to be authentic. Marianne and Héloïse maintain their truths when recounting their past and a bond begins to grow over conflicting interpretations of their experiences under patriarchy. The contrast reflects a level of mutual equality overshadowed by Marianne secretly painting Héloïse. Regardless, their vulnerability creates a slow burn. Marianne finishes the painting, requests that she is able to show Héloïse and tell her the truth– the Countess agrees.

Marianne shows Héloïse the painting and the two argue over what a good portrait consists of. Héloïse’s image looks like a complication of fragmented memories rooted in “rules convention, and ideas.” It was a presentable portrait yet as Héloïse pointed out “I find it sad it isn’t close to you (Marianne).”

The scene follows:

Héloïse: “That’s me?”

Marianne: “Yes.”

Héloïse: “Is that how you see me?”

Marianne: “It’s not only me.”

Héloïse: “what do you mean, not only you?”

Marianne: “There are rules, conventions, ideas.”

Héloïse: “You mean there is no life? No presence?”

Marianne: “Your presence is made up of fleeting moments that make lack truth.”

Héloïse: “Not everything is fleeting. Some feelings are deep.”

Marianne, displeased with the feedback she receives (mostly looking displeased with herself) destroys the painting. When the Countess sees the painting; she turns to Marianne and calls her “incompetent” for not creating a finished product that would persuade the Milanese gentleman. Off screen Héloïse interrupts the Countess’ roast of Marianne and says steadily “She’s staying, I will pose for her” leaving both the Countess and Marianne stunned.

Héloïse accepts her fate while understanding Marianne’s former struggle painting her in secret. Marianne is a woman painter in 18th century France and Héloïse is the daughter of a Countess set to be married to a Milanese suitor. Like Marianne attempts to be empathetic of Héloïse’s inevitable fate by showing her a different perspective; Héloïse steps in to show both her mother and Marianne a different side to her personality. It is through the reclamation of choice that Sciamma is able to show the strength of Héloïse despite her tragic fate. The Countess gives the pair 5 days (the time she will be away from the island) to finish.

Starting right away, Marianne and Héloïse begin to paint and we are left with a familiar shot of hands using charcoal on canvas. After the first day of work Marianne is shown getting cramps signifying the arrival of her menstruation cycle. She seeks out Sophie for help. Sophie assists and reveals that she is planning an abortion for a current pregnancy so she hasn’t had her period. She shares with Marianne that she “was waiting for Madam to leave to see to it.“ Marianne and Héloïse assist Sophie’s choice by helping her search for an herb that may work (18th century abortions). They end the day inside the castle where we see some “yearning but withholding” tension between Héloïse and Marianne.

Marianne struggles with her feelings verbally in the following scene. Héloïse is posing for her painting when Marianne says, “I can’t make you smile. I feel I do it and then it vanishes.”

Héloïse: “Anger always come to the fore.”

Marianne: “Definitely with you. I didn’t mean to hurt you.”

Héloïse: “You haven’t hurt me.”

Marianne goes on to point out several things that Héloïse does when she feels a certain way and ends with “Forgive me, I’d hate to be in your place.” Héloïse, seemingly annoyed, responds “We’re in the same place, exactly the same place… [sic] If you look at, who do I look at?” Here she is referring to the feelings between herself and Marianne as well as the connection she has as the muse for the painter (both women are observing each other).

After a night of card games, Héloïse vocalizes interest in Marianne’s artistic practice when she inquires as to how Marianne is able to paint men given that she just said the prevention of women painters painting men, “(is) mostly to prevent us (women) from doing great art.”

Marianne states, “without any notion of male anatomy, the major subjects escape us.” Héloïse chooses to turn the subject back to women by asking Marianne to share with what she tells her models when she is painting them. Marianne obliges by offering a slew of traditional compliments often made by men to women.

Sciamma often drops the mention of men before quickly turning it back to the Marianne’s story from her perspective. The lack of men in the film isn’t a lack of patriarchy. On the contrary, patriarchy lingers over the film as the story unfolds. It is just on the outskirts. Sciamma is able to depict women in holistic complexity while depicting how women interpret, think, and analyze literature (the property of intellects-accessible to men).

Héloïse reading the story of Orpheus traveling through the underworld to persuade the gods to let his love (Eurydice) live again while Marianne and Sophie listen is a rare scene in cinema. In this scene, each character is granted their own perspective as to why they believe Orpheus broke Hades one condition that would have allowed Eurydice to live again. Orpheus turns around to look at Eurydice causing the gods to bring her back into the underworld.

Sophie argues, “Poor woman. Why did he turn? He was told not to but did, for no reason.”

Marianne states, “I think Sophie has a point. He could resist. His reasons aren’t serious. Perhaps he makes a choice… He chooses the memory of her. That’s why he turns. He doesn’t make the lover’s choice, but the Poet’s.”

Héloïse offers, “Perhaps she was the one who said, “Turn around.’”

It is through discussing these very different perspectives that we see how Héloïse views love in relation to Marianne’s interpretation. Héloïse believes there is a possibility that Eurydice had the agency to speak her desires while Orpheus made the poet’s choice in the story. The two decisions could exist in one story.

After the Orpheus reading the three attend a bonfire where Sophie learns that she is still pregnant. Héloïse and Marianne gaze through a large bonfire showing viewers the desire rising between them.

The next day, Marianne and Héloïse walk on the beach, find a cave, and consent to a kiss. Héloïse pulls away from Marianne after the kiss but is waiting for her in her room that evening. Marianne pauses at the door and turns around only to see a ghostlike figure of Héloïse in a wedding dress. This figure haunts Marianne’s retelling possibly because it’s the last image she has of Héloïse. We learn this later. The story continues with her entering the room and the two have a brief conversation before spending the night together.

Sophie wakes them up the following day and the three venture to a medicine woman where Sophie has the abortion. This scene forces viewers to watch and when Marianne looks down instead of at what is happening in front of her; Héloïse tells her to “look.” All three women return to the castle where, with the encouragement of Héloïse, they paint Sophie’s abortion experience.

Tensions between the two lovers begin to develop as the inevitable end of their relationship nears. They argue over the painting that is to seal Héloïse’s fate. Héloïse leaves the room and Marianne looks for her in the castle. She runs into Sophie who informs Marianne that the Countess will return the following day. Sophie asks, “Will you be ready?” To which Marianne responds “yes.” Marianne finds Héloïse at the beach and they cry together before returning to the castle to finish the painting.

Marianne requests that Héloïse stand beside her to finalize the portrait together. “When do you know it’s finished?” Héloïse asks. “At some point you just stop.” Marianne responds.

The way this film is written shows the struggle of women through different experiences and identities. It relates to the choices they make and the agency of each woman to make those choices. Marianne is talking about both painting process and the inevitability that a relationship between the two would be possible. She is accepting the end to their relationship and respecting Héloïse’s decision to finish the painting instead of destroying it.

The following scenes shows the mutual strength that has been established by developing full women characters. The two are vulnerable, honest, and true to their feelings in these final scenes together. Marianne asks Héloïse to “remember” instead of “regret” to which she commits.

Upon her return, the Countess reestablishes patriarchal control and demands Héloïse follow her outside Marianne’s room when Héloïse asks for a minute with Marianne. At this point, the painting has been approved and Marianne has been paid. Instead of a goodbye between the two lovers, we get a shot of the painting resting face up in a carrier crate. The boatman closes the crate much like one would a coffin and nails it shut alluding to the old saying “nails in a coffin.” Héloïse looks back before exiting the room.

Sophie comes to say goodbye to Marianne; they hug. Marianne takes a deep breath before entering to say goodbye to the Countess and Héloïse. She enters and Héloïse is in a wedding dress. The fire place is not lit in this scene signifying the end of their romance. Marianne awkwardly hugs the Countess before making her way to Héloïse. She hugs Héloïse tightly for a moment and sprints down the stairs towards the front door. As she gets to the door, we hear Héloïse say, “Turn around.” Marianne obliges and the door is slammed shut forcing us back into real day.

Marianne finishes the class noticing one of her students made her look sad in her painting. She says, “You made me look sad.” Her student responds that she was sad and Marianne says that she is no longer.

Marianne narrates the last 2 scenes by remembering the times she sees Héloïse after leaving the island. The first time is in a portrait at a gallery exhibit where her own painting was on display under her father’s name. She sees her next at an orchestra where they play Vivaldi’s Four Seasons—a tune that she played Héloïse when at the island. Marianne views Héloïse across the theater and says, “she didn’t see me.” Marianne watches Héloïse once again as she travels through memories of their love. Héloïse cries at times, smiles at others, and vividly remembers Marianne. The movie ends leaving viewers in their own feelings/memories.

The film shows this complexity by allowing the viewer to see how women navigate systems of power and how they can see agency within their individual choices. While Héloïse ends up marrying the Milanese suitor, she still makes the decision to say “Retourne-toi” closing the relationship in order to remember it. Likewise, Marianne decides to honor Héloïse’s request by literally turning around to say goodbye. Women make complex, yet limited, decisions in Portrait of a Lady on Fire and justifiably so given they are navigating a complex heteronormative/male dominated society. I write with the assumption that Sciamma named Sophie intentionally to evoke the Sophie’s choice definition

This film cannot have a happy ending for many reasons: patriarchal norms/expectations, time period, financial status, sexual orientation of the two characters, etc. What can happen is, through remembering, the two main characters manifest a love that withstands power. It is hidden away in the color decisions of Marianne’s paintings and on page 28 of Héloïse’s book.

Sciamma focuses on is the experiences behind the final art piece as opposed to accepting art for what it is. What were the experiences of the muse? What was the experience of the painter? What feelings are evoked in looking/being looked at? How do we see it differently based on experiences? These are the questions Sciamma beckons with her writing and directing.

She asks you to look beyond the storyline to will see that sometimes it does get better for LGBTQIA+ identified individuals. Sciamma was bold enough to show us how far we have come (from invisibility to visibility) and allows us to individually reflect on how far we have to go (from unaccepting of LGBTQIA+ love to accepting). She conceptualizes a love story where both characters knowingly make the ultimate sacrifice for the future good.

Héloïse chooses a marriage outlined by her mother so Marianne can move up in social status. Marianne, using her new claimed status, continues to foster the social shift towards equality by training a new era of women artists. Both characters continue to resist patriarchy by remembering.

Héloïse reading Orpheus

Jennifer Meneray is a feminist writer based in Washington D.C., USA. She takes pride in social justice activism and using her skills to elevate artists existing/working in the margins of the mainstream. She curated and is current editor of the blog Your Friendly Feminist.