The persistent dream of a “gay utopia” is one of the constants in gay and lesbian historical imaginings over the last 200 years.

In recent years, we have seen significant advances won for LGBT rights through hard-fought legal cases and well-targeted political campaigns. Yet it is worth remembering that for decades, recourse to such methods was not available to LGBT people. The law-court and the parliament were deaf to their pleas. For many, it was only in their dreams that they could escape oppression.

One should not underplay the importance of such fantasies. They provided succour and hope in a grim world. It was comforting to imagine a time before Christianity told you that the acts of love that you committed were a sin or the law pronounced that your public displays of affection were acts of “gross indecency”. The persistent dream of a “gay utopia” is one of the constants in gay and lesbian historical imaginings over the last 200 years.

One place in particular attracted the longings of gays and lesbians.

This was the world of ancient Greece, a supposed gay paradise in which same-sex love flourished without discrimination. It was a powerful, captivating dream, one which scholars of ancient Greece have started to pull apart, revealing a culture in which homosexuality was much more regulated and controlled than previously thought.

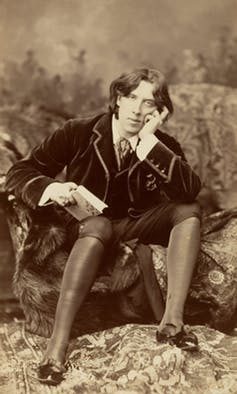

Oscar Wilde tapped into this longing for a time and place free from moral censure in his famous “Love that Dare Not Speak Its Name” speech. The occasion of the speech was his criminal trial in April 1895 when Wilde was asked to explain the meaning of the seemingly incriminating phrase “the love that dare not speak its name”, a phrase which was found in the poetry of his companion, Alfred Douglas. Was this a coded reference to indecent passions, asked the prosecutor. Wilde’s response has become a classic of homosexual apologia:

“The love that dare not speak its name” in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect … It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.

In this spirited defense of same-sex love, Wilde created a genealogy of historical moments in which homosexual love had blossomed. He rewrote straight history and offered a different version of the past in which his own 19th-century passion joined a continuous tradition that stretched back to the very foundation of European civilization.

He sought to recover a love that time and prudish censors had tried to erase. From the days of the Old Testament through to the flourishing of culture in Greece and the Renaissance, Wilde sought to bear witness to a gay past of free romantic expression.

All roads lead to Greece

According to contemporary newspaper accounts, Wilde’s speech was greeted with loud and spontaneous applause from the courtroom’s gallery. Yet for all its brave defiance and elegant phrasing, there is little in it that is truly original. The rhetoric Wilde advanced had been in circulation for decades. Any educated homosexual in the 19th century could have given you a speech along much the same lines, citing the same canonical figures and possibly a few more. Wilde was tapping into a shared gay fantasy about the past, a fantasy in which one culture stood out above all others, the world of Classical Greece.

It is hard to overstate the affection with which 19th-century homosexuals like Wilde viewed the Greek world. Here was the utopia that they dreamed about – a place in which homosexuality was not only accepted, but celebrated. The legacy of this tradition was so potent that many felt even when visiting modern Greece that it was still possible to feel the traces of this passion.

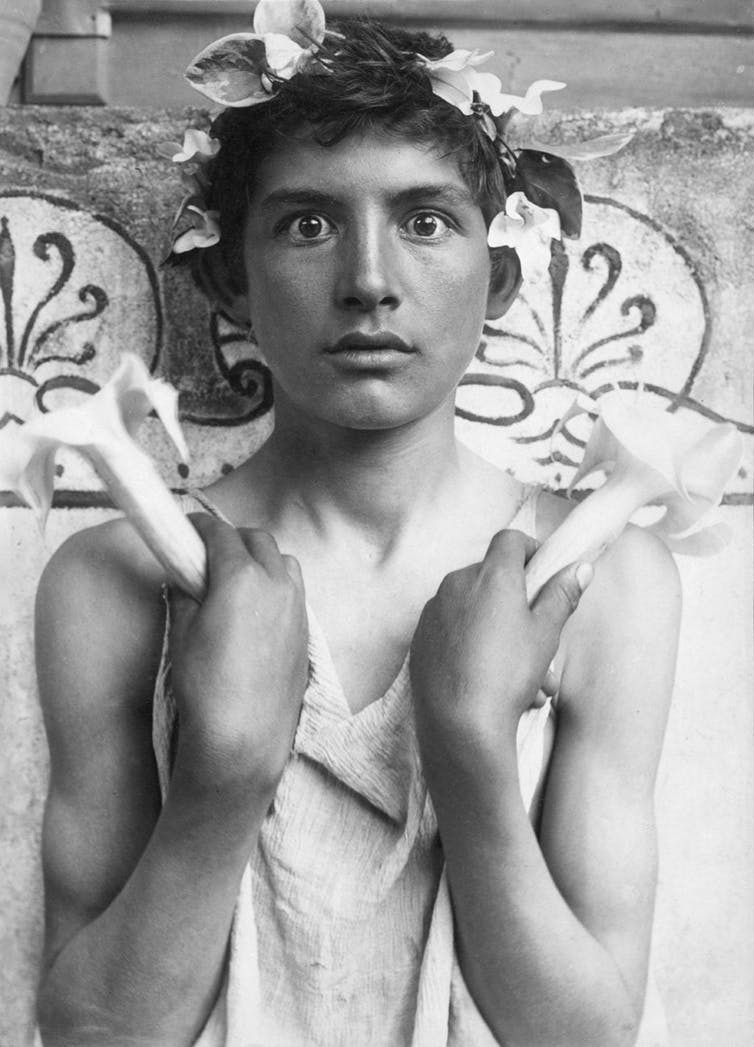

In the warmth and light of the Mediterranean, numerous 19th- and early 20th-century gays and lesbians sought to fleetingly recapture visions of this lost paradise and recreate it amongst its ruins. Photographers such as Wilhelm von Gloeden and his cousin, Guglielmo Plüschow, working in Sicily staged local youths with props and poses that were designed to evoke this lost world.

Looking at these images today, it is hard not to be struck by their sense of desperate, wilful escapism and rejection of the contemporary world and all that it offered, even as they used the latest photographic techniques in creating these tableaux. Quite what their Italian models thought of these odd Germans and their desire to dress them up in wreaths, togas, and splay their bodies on leopard skin rugs remains a mystery.

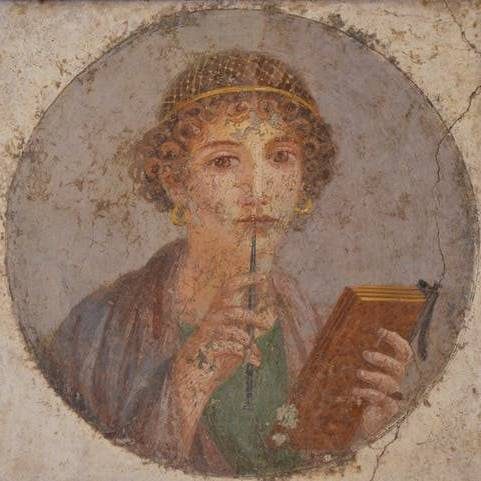

In a similar vein, numerous lesbians travelled to the Greek island of Lesbos. For many this was an act of pilgrimage arising from a desire to visit the home of Sappho, the archaic poet whose passionate, lyrical evocations of female same-sex desire became so famous in antiquity and beyond that women who were sexually attracted to other women came to be named after her island home – a nomenclature that not even a legal action by outraged inhabitants of the island can stop.

The Anglo-French poet Renée Vivien and her lover the American heiress Natalie Barney tried to set up an artist’s colony on Lesbos in 1904. It was ultimately unsuccessful. Vivien then retreated to Paris where she held wild salons instead, complete with replica Greek temples and recitations of Sappho’s poetry.

This legacy continued well into the 20th century, so much so that the homosexuality of the Greeks probably counts as one of Western culture’s worst kept secrets. Every time that the legal rights of gays and lesbians have been discussed, somebody will evoke the Greeks.

Indeed, the association between Greece and homosexuality is so strong that even anti-same-sex marriage advocates are not above using it to support their arguments. In the US Supreme Court case that legalised same-sex marriage, one of the dissenting judges, Justice Samuel Alito noted that while the Greeks and Romans approved of homosexual relations, they never created an institution of same-sex marriage. In his opinion, the only conclusion to draw was that the Ancients must have regarded same-sex marriage as an institution that would cause harm to society.

We have seen the same argument used against same-sex marriage in Australia. Both former senator Bill O’Chee and Dr John Dickson, the founding director of the Centre for Public Christianity have run similar arguments about the absence of same-sex marriage amongst the Greeks.

Not such a paradise after all

It goes without saying that the arguments offered by Justice Alito and his followers are deeply flawed. There are numerous institutions which the Greeks and Roman would have resisted (the right of women to vote, for example) that even the most arch conservative must accept are a good idea. Nevertheless, these arguments do point to some of the dangers of relying on an overly romantic view of the Greeks and their attitudes to same-sex love.

The Greek attitude to same-sex attraction was not nearly as permissive or free as many have assumed. Any idealised view of the Greeks falls apart the moment one remembers – and yet how easy it seems to be to forget – that ancient Greece was a society where slave-ownership was prevalent and that slaves were regularly sexually exploited by their masters. Yes, the Greeks tolerated same-sex attraction, but they also tolerated the violent sexual abuse of men and women in a manner that nobody could countenance today.

Even amongst free-born men, Greek same-sex courtship was highly regulated. Older men pursued younger boys, and it is hard not to see an inherent power imbalance in such relationships, even if the older man is completely smitten. There were elaborate protocols regulating the process of seduction. There were rules about the kinds of wooing gifts that could be used. Dried fish and fighting cocks were the ancient homosexual equivalent of flowers and chocolates.

Boys should not appear too eager. For the suitors there was a fine line to walk between looking keen and looking like a besotted fool. Violating these rules lead to social death: slut-shaming seems to be a universal human tendency. We have numerous accounts of same-sex affairs that go badly resulting in murder and suicide. In one case, a disappointed lover hanged himself at the door of the boy who rejected him. In another case, one man tried to murder another over the affections of a slave boy.

We know very little about the lives of same-sex attracted women in Greece. Our best evidence remains the fragments of poems of Sappho that have come down to us. Yet even here, the picture is not entirely rosy. Sappho’s poems are often tinged with melancholy over love rejected or made impossible through forced marriage.

Love among the gods

Myths relating to homosexual love also rarely end well. One of the foundational myths for the establishment of same-sex love in Greece concerns the legendary figure of Orpheus. This musician is best known for descending into the underworld in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to retrieve his wife Eurydice from the clutches of death.

What is less well-known is that following this attempt, he gave up entirely on women and instead turned his attention to young men. Indeed, he was so successful in proselytising for homosexuality that he upset the local female followers of Dionysus, the god of wine and drama. Outraged at Orpheus’ rejection of women they tore apart the musician and dismembered his body, throwing his head into the nearby Hebrus river where even in death it miraculously continued to sing.

Passion, jealousy and death are repeated motifs in Greek homosexual myths. The god Apollo’s beloved Hyacinth was killed when a jealous lover, the wind-god Zephyrus, diverted a discus into the skull of the young man. Out of the blood that was spilt grew the first hyacinth. It is a tragic, moving story that deserves to be better known. Oscar Wilde popularised the green carnation as a symbol of homosexuality visibility. It is high time to do the same for the hyacinth and rescue the bulb from its dowdy fusty retirement-home image and make it fabulous again.

Even being the strongest man in the world can’t ensure the safety of your loved ones. Hercules lost his boyfriend Hylas to some conniving nymphs who drowned the boy in a pool. The hero was so distraught at the loss of his lover that he abandoned the quest for the Golden Fleece. Hercules’ other male lovers didn’t fare much better. Sostratus died young. Abderus was consumed by man-eating horses.

Love and strife

These myths point to an ambivalence that runs through Greek society about same-sex attraction. Male same-sex relationships attracted particular care and supervision in the Greek world because the freedoms that men, unlike women, enjoyed meant that there was always greater potential for things to go wrong. If left to get out of control, passions could have tragic consequences. It is little wonder that thinkers like Plato turn out to have an ambiguous relationship towards same-sex relationships.

Sometimes Plato seems to regard same-sex couples as the very pinnacle of the ideal relationship. In Plato’s Symposium, one of the speakers, Aristophanes, sketches out a vision of same-sex love which closely approximates modern notions of companionate relationships, a place where equals meet and their love completes each other. It is a beautiful vision, but one that seems to be more of a thought-experiment than a reflection of lived reality in ancient Athens.

At other points, such as in his Laws, Plato is dismissive of same-sex relations, regarding them as unnatural and not fit for proper society.

The picture of same-sex relations that we get from Greece is a complicated one. Nevertheless, all the efforts undertaken by the Greeks to regulate these relationships does challenge us to consider why societies are so frightened by love, not only gay, but straight desire also. What is it about this emotion that causes a culture to attempt to reign it in through complicated systems of courtship or invent a series of myths to scare you about committing yourself too completely to someone?

Studying attitudes to same-sex love amongst the ancient Greeks is a salutary reminder that there is a difference between history and nostalgia, and it is dangerous to confuse them. No longer looking at the Greeks through the rose-coloured lens of escapist wish-fulfillment reveals a culture that is complex and diverse in its attitudes and behaviours. The Greeks become a little more disappointing, but also more real. There are lessons to be learnt, but they do not come from imitation. A gay utopia may be possible, but it is a project for the future, not a lost relic of the past.

Alastair Blanshard, Paul Eliadis Chair of Classics and Ancient History Deputy Head of School, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.