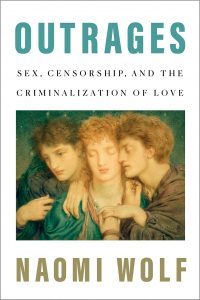

Newly updated, first North American edition — a paperback original — “Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love” by Naomi Wolf.

From New York Times bestselling author Naomi Wolf, “Outrages” explores the history of state-sponsored censorship and violations of personal freedoms through the inspiring, forgotten history of one writer’s refusal to stay silenced:

I never thought I’d be a professional feminist as a career choice; I certainly didn’t intend to be. Growing up in the Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, at the height of various social justice movements in the 1970s including the fight for LGBTQ rights and the agitation of the “second wave” of feminism, I thought that by the time I was an adult, all of these battles would surely be won.

Sadly they weren’t. When I wrote The Beauty Myth at 26, which happened to be published when a new generation was seeking a way out of the torpor and “backlash” of the evil 1980s, I named in the book, and engaged with, what became known as the “Third Wave” of feminism. (Writer Rebecca Walker coined the phrase at the same time).

This led me to an unusual life opportunity: I happened to have a seat as an observer of (and at times a participant in) the drama of Western feminism for the next thirty years.

The headline is that the women’s movement has gotten smarter and better, and that we are in what I’ve called elsewhere, a Renaissance moment for feminism.

This is hard at first, I am sure, to believe since mainstream media, which is still reactionary when it comes to women, rarely documents our vast successes.

News outlets still like to feature the battle for women’s rights in a few stereotypical ways. At best a story will run about women’s systematic victimization – which is all too real; but the huge efforts that go into our effectively pushing back — landmark court cases, giant settlements against employers, rapists put in prison, traffickers undone by good legislation, even gradual transfers of larger shares of wealth to women as they open businesses, drive companies’ profits and fight for equal pay – are downplayed or ignored.

So women don’t see reflected in the news, many benchmarks of how very effective we are being accruing decades of revolutionary victories.

A reason that we are being so very effective as what is basically the most sweeping revolution in history also has to do with how feminism has grown and gotten smarter since the 1970s.

When I was in my twenties, a painful fact was that feminists of my generation had to start all over again simply explaining (and learning) what equity issues were; simply re-teaching and reiterating what most students who take gender studies today, see as Feminism 101; basic theory. In the 1990s, things were a mess: the first insight of feminism – it’s not my personal problem, it’s systemic, it’s Patriarchy – was hard for many women to achieve, as the analysis had been swept away and they were being told that their problems were personal, not political.

The accomplishments and analysis of my mom’s generation, the Second Wave, had been erased in a very short time. This left younger women to grope in the dark, figuring out the basics of body image issues, pay inequity, work/family balance struggles, sexual and domestic violence traumas. But when Third Wave feminism arrived, with books such as Susan Faludi’s Backlash and Rebecca Walker’s collection To be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism, younger women joined forces with enthusiasm.

Western feminism at the end of the 20th century, and into the 21st, had flaws. One central flaw was the fact that at first, white women’s issues and issues relating to women of more affluent economic classes, were often seen (or portrayed) as being central. An example of how simply bad a situation this created, from my own experience, is the fact that for a decade, I was invited onto panels – often made up only of white women – that were asked about “the conflict between mothers who worked and mothers who stayed home”, as if that was “feminism” – as if that the biggest problem that women of all backgrounds, faced.

A needed critique from women of color and women across the economic spectrum, forced a welcome upheaval in the form of a call for “intersectionality.”

This critique was made easier by the fact that women’s (and later gender) studies programs had been established at many universities, thus giving feminist ideas institutional continuity that had eluded the Second Wave. One hugely positive result of this critique is that the image of the leadership of the women’s movement shifted, and more people became aware that women’s issues were diverse depending on whom you were, and that feminism was global; and that the most exciting advances and most important theory were being spearheaded by women in the Global South, and often presented by leaders of color.

Another problem in the past was divisiveness. During the Second Wave, sexual identity could be a battleground. Earlier feminism could be extremely Puritanical and judgmental about other women’s choices. Straight women such as Betty Friedan criticized lesbians, as in her famous 1969 warning about the “lavender menace.” Some groups, such as Radicalesbians, organized a reaction to this, and developed influential theories of “woman-identified women” that were exciting, but that also seemed to critique straight women for false consciousness.

Women who identified as bisexual faced criticism too, for “not making up their minds.” This judgmental approach endured into the 1980s and early 1990s. Critique often turned women against each other.

Third Wave feminism was a huge step forward in that this group rejected the rigidity, divisiveness and judgmental tone of our moms’ era, creating a more inclusive discourse that was more open to the fact that women made different life choices and had different political agendas, and that there was space for all.

Fast forward to today. There’s never been a better time to be a young feminist, or a better feminism. The young women I meet today have rejected a lot of stupid binaries that have held people in thrall for the duration of history.

Fast forward to today. There’s never been a better time to be a young feminist, or a better feminism. The young women I meet today have rejected a lot of stupid binaries that have held people in thrall for the duration of history.

They usually aren’t wedded to the idea that there are only two genders; they often celebrate the fact that gender is a spectrum, as they see it, and that it can be chosen. They have the important language and concept that sexuality can be a specific identity and/or it can be what they call “fluid” – a word and acceptance that could have liberated so many people in the past, had it been in usage.

They are self-aware about white privilege, very often, and scan their own positions for unintended (or intended) racism or class blindness – a self-awareness that is often mocked by the right wing, but that is so much better than the obtuse omissions caused by the narcissism of privilege that often afflicted my own generation.

Younger feminists today have little fear of power or of making a scene in a good way; they are rarely burdened with spectres of what “nice girls don’t do”; they use social media, take to the streets, start blogs and businesses, out their harassers and rapists, choose their own body positivity, make their own family structures, decide their own fates, form their own alliances. I’ve never met a generation less impressed with others telling them what to do and whom to be. The world they are making for women – however you or they define that word – is going to be a world of radical freedom — if only pandemics and oligarchs don’t stand in their way.

Feminism has grown up, in my view, with this generation; and become as fluid and inclusive and diverse as is the human family.

And that’s a victory we can all celebrate.